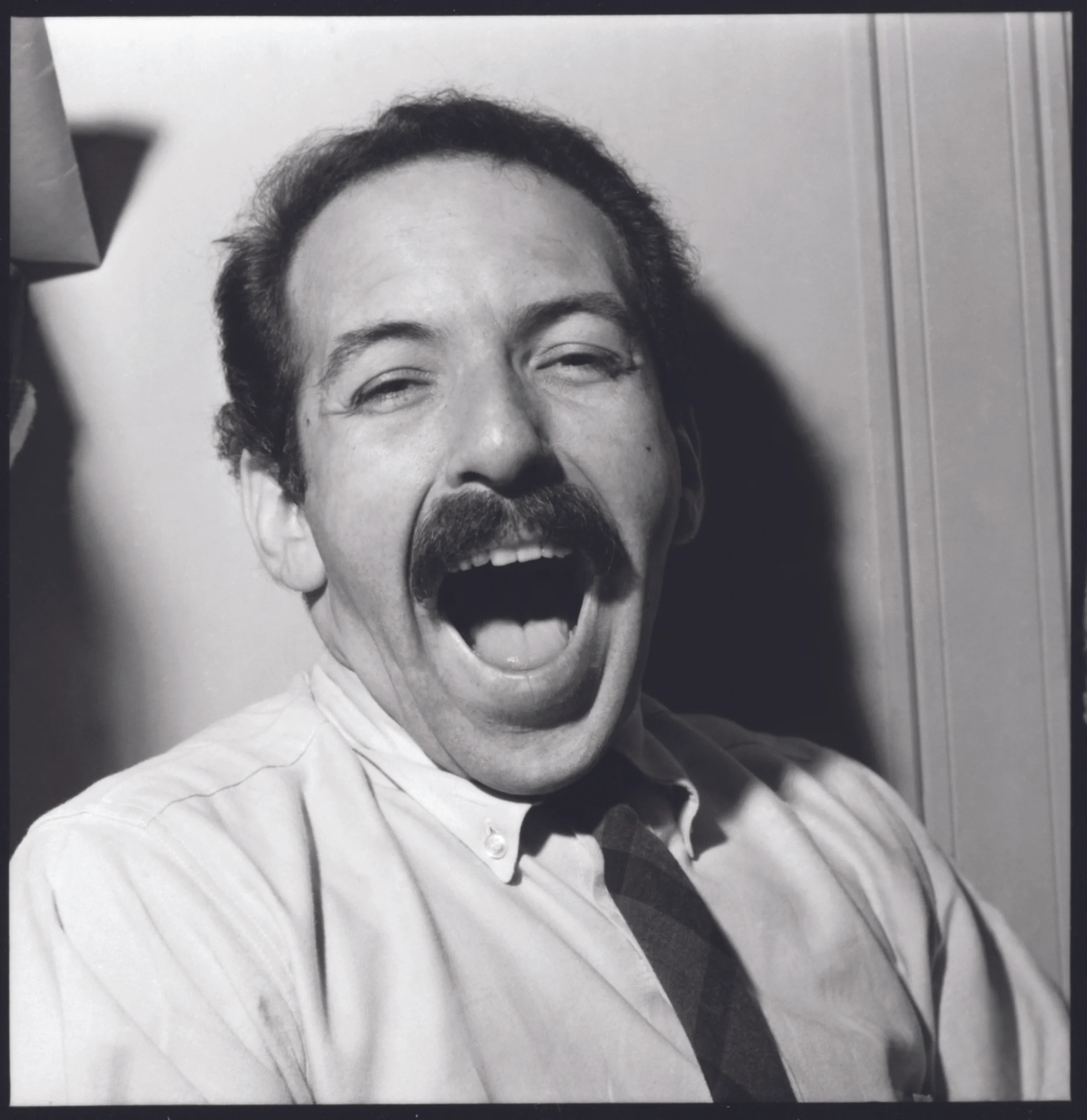

Gerald Davis was born in New York City in 1940 and grew up in a working-class family in the Bronx. His wife Karen remembers, “From his mother he learned about warmth and caring for people; from his father he acquired a sharp sense of humor; and from his brother he learned about the necessity of leaving the Bronx and venturing in Manhattan and beyond.”

While a student at City College of New York studying petroleum technology, Davis started to learn about photography through part-time work at The New York Times and UPI photo libraries, and visits to the Museum of Modern Art. In 1955 MOMA debuted a groundbreaking show of photography, curated by Edward Steichen, called The History of Man. The show, featuring works by 273 photographers from 63 countries, was hugely influential to Davis with its human and humane depictions.

Davis’s only formal study of photography was at The New School for Social Research with iconic photographer Lisette Model, whom he loved learning from. Model’s influence is as clear in Davis’s work as it is in the works of another noted pupil, Diane Arbus.

Karen notes, “The technical aspects of photography he learned by studying photographs. He did all of his own black-and-white printing early on. He was in many ways self-taught. He interned for other photographers; [he] was a studio assistant. Once while assisting the photographer Myron Dorf on a Thanksgiving shoot, Gerry brought home the golden-hued turkey that was used for the photographs. We sat down to eat it, and after cutting into it, [discovered it] was raw, having been only painted and oiled for the shoot.”

Davis met and married Karen in 1966 after a chance meeting through friends at a free concert by City College in New York City. Karen remembers, “After the concert we went to a bodega, got some wine and cheese, and went for a picnic on Riverside Drive; and as they say, the rest is history. I admired his sense of humor and perspective. With his October birthday I said he was a trickster but my treat.”

Karen was a journalist and worked often with Davis on stories:

“We did a tour of the Southwest for the British magazines. We shot celebrities like John Wayne on location and Vincent Price, who had a fabulous Indian art collection that made me very jealous. As the journalist on the story, I barely noticed Gerry shooting, he was so was unobtrusive. He was very good at loosening up people.

“He was also a very risky photographer in a sense. We were in Guatemala, and we went to a big church at the top of these steps where religious ceremonies go on. Despite the ‘No Photography’ signs posted around, he would just drop his right arm, the other holding the camera and just shoot away. He had no fear. He would sometimes direct his subjects loosely, but he was not very controlling like a fashion photographer might be.”

Vanessa remembers, “He would do anything for a shot. There was a farmer who had fainting goats. To get the shot he tried to get all of the goats to faint at once by running down the hill and bellowing. However, only he fell and broke his ankle, and the goats, they didn’t bat an eye.”

Karen says, “Gerry loved photography, but he lived for his children.” It seems his daughters, Ariella, born in NYC in 1973, and Vanessa, born in 1978 in West Palm Beach, feel exactly the same way. Ariella said Davis was, “The best dad in the world; not only did I think that but all of my friends did too. The warmest, funniest, most understated guy to be around, he always made you feel good.”

To rid the girls’ rooms of worries, Gerry would put the kids to bed reciting, “Hocus pocus, jiminy focus, monsters and witches, ghost and goblins, cops and robbers, and everything that’s bad (including giants) STAY AWAY!” Karen notes. “I think what is significant is Gerry’s use of the word ‘focus.’”

Ariella remembers that as a child. “I knew he had an interesting job because he traveled constantly, and I was thrilled when he came home. He would tell us these crazy stories about who and what he had photographed—Twiggy, the water skiing squirrel— I knew that other dads weren’t doing that. Having him for a dad was a good role model.”

Vanessa recalls her father’s passion for the arts: “He loved movies, and he loved music. He loved classical music, an appreciation that he shared with his brother. The other night, I saw this concert by a woman who was pregnant and it reminded me of a letter that he wrote to me when I was at camp about seeing a woman, a busker in downtown West Palm Beach. He wrote how her voice was so beautiful it took his breath away. He definitely was very sensitive towards the arts. He talked about sitting in front of Picasso’s Guernica for a really long time and just … contemplating it. I think he was really in the mix; he had a lot of photographer friends. They were always coming to our house and visiting and staying with us. He was very involved in the photojournalism community.”

Karen said, “He admired lots of photographers: Lisette Model, Herb Ritts, Henri Cartier-Bresson; we would talk about the nudes of Bill Brandt, they reminded him of Jean Arp.”

After returning home from a job, Ariella remembers, “Dad was always looking at slides on this giant wooden light box with a magnifying glass. He would call me in and ask me which ones I liked, tell me about the kind of lighting he used. I remember just hanging over his shoulder looking at the light box. When he came home from shooting the nudist colonies I asked him if it was weird. He said, ‘No, they were just doing normal things we all do, just without clothes.’ Dad said he felt awkward being the only clothed man in the room. He was very nonchalant about the stories he worked on. He loved shooting and traveling and that it provided a way to feed his family.”

Vanessa notes, “Dad definitely had a wicked sense of humor. I think his two strongest character traits were that he was critical, but funny. I really think that when you look at the photographs, it’s like you are seeing through his eyes. There’s just so much that’s being expressed non-verbally. I just think it’s awesome that he raised a family making [these] colorful, creative, exploratory works.”

In 1964, Davis became a photographer and editor for United Press International in their New York Bureau covering everything from opera to transit union strikes. When Manchete, a Brazilian general interest and news magazine similar to Life, opened a New York bureau in 1968, he became a staff photographer and eventually photo editor for it and several of its sister publications, which focused on nature, travel, fashion, and celebrity news.

Davis became the first managing director of Contact Press Images in 1976, helping founder Robert Pledge develop the photo agency into one of the industry’s most prestigious photography agencies. He moved his family in 1978 to West Palm Beach, Florida, where he briefly, yet memorably, became photo editor for the National Enquirer. His two years there yielded quite a few notable assignments, like the notorious photos of Elvis Presley in his casket. After leaving the National Enquirer, Davis worked freelance for the rest of his life. His client list includes most of the major British, European, and U.S. national publications. In addition to photojournalism, he was also excellent in the studio, often shooting portraits of business executives and celebrities, as well as fashion and still life.

Davis would often take his daughters with him on shoots, putting them to work as assistants. Ariella notes that, “Every shoot was kind of a take-your-kid-to-work day. Once on a trip to a job in the Florida Keys, we just pulled over to admire the sunset.”

Sometimes the assistants had other duties like talent wrangling or modeling, as was the case when Vanessa posed with Americas’s largest cat. “Posing with that cat was fun, but once on a trip to California we were staying at the Four Seasons in Beverly Hills, and this B-Movie movie star, Russ Meyer sex kitten lady, Edy Williams, came and met us to have dinner. I was twelve years old at the time, and I didn’t know or care who Edy Williams was. I was just, sort of, horrified by this woman. She seemed really old to me, and she was wearing this ratted, matted blond wig with a blue satin ribbon hanging out of it and a really skimpy dress. I just remember her endlessly talking about herself, and I never had such a negative reaction to someone. I just had to get away from them, so I asked to be excused. But my dad was very bemused by the whole thing, but I don’t think that he disagreed that she was a challenging personality. But he was an adult and knew what the deal was.”

Karen remembers, “Gerry’s photographs reflect his personality and vision of the world—the humor and warmth of people and the grandeur of nature—and he never outgrew his passion for photography. ‘There’s a difference between making pictures and taking pictures, which most people don’t know. I make them,’ he would say frequently. Gerry never thought of retiring from photography. ‘What do most people do when they retire?’ he’d say. ‘They come to live in Florida and do what they’ve been wanting to do all their lives. I moved to Florida at age 37 and get paid to do what I’ve always wanted to do—go out into the world and make photographs.’

“His ‘boyishness’ stayed with him all his life and was an invaluable asset in his career as a photojournalist. It helped him approach assignments in fresh ways, whether it was a cover story of an executive for Business Week or a feature story on a bald-headed men’s convention. It allowed him to disarm, get close to, and capture the essence of his subjects whether they were the Sultan of Brunei, allergy victims, or children in the streets and alleys of third-world countries.

“While he was working on Black Tie in Paradise it required shooting a lot of social events. A fellow photographer told me while the other photographers were shooting like crazy, Gerry was hovering around the outskirts of the room looking for the right shot, very selectively. His society pictures are not standard society pictures, like women with their hands on their hips or couples leaning their heads into each other. In a way it feels like candid photography.”

I wondered if any of Davis’s subjects ever bristled at their depictions. Vanessa notes, “Overall, some of the people had a sense of humor about themselves—or about just their lives in general. Because he wasn’t making fun of them, he’s just sort of presenting them as they are with all of the inherent humor, there wasn’t really anything to criticize.”

Davis worked often with his long-time friend, the British journalist Rodney Tyler, on a variety of stories. He remembers an assignment about a socialite and a pig she was trying to save from being banished from Houston. “Gerry turned out to be, quite simply, the world’s loveliest man. I know of no one who did not fall under his spell. He could literally charm in an instant. I will tell just one story; it concerns a very difficult interview with a woman called Carolyn Farb, who despite being one of the world’s richest divorcees, was nevertheless severely lacking in the looks department. She was also suspicious and aggressive. For thirty minutes I struggled with severely monosyllabic Ms. Farb to no avail. All she would say was ‘yes’ and mostly ‘no.’ Eventually I gave up, gestured toward Gerry and said, ‘Mr. Davis would like to take some pictures of you.’

“She shook her head and uttered the most emphatic ‘No’ of the afternoon.

“Gerry looked at her for a moment—then he looked at me and grinned—and then he said: ‘Mrs. Farb—may I call you Carolyn—has anyone ever told you are beautiful?’ She melted. He got the pictures—and I went back to the hotel, outraged that the man could tell such lies for his art. There were stories on chickens with contact lenses, the poodles that pulled sleds in Alaska, Ruby the painting elephant, and our favorite of all time, the cows in Kansas that wore bras. All these stories and dozens of others sprang from our shared sense of fun. I found in Gerry a man who loved to laugh. He loved life’s absurdities.”

In 1997, while home between assignments, Gerald Davis died suddenly in West Palm Beach.